Caricature is often mistaken for simple humor, a playful distortion meant only to amuse. In reality, it is one of the most precise and revealing visual languages ever developed. At its core, caricature answers a basic human curiosity: how can exaggeration bring us closer to truth rather than further from it? By stretching facial features, gestures, and expressions beyond realism, caricature artists uncover something essential about personality, power, and perception.

Within the first moments of encountering a successful caricature, recognition happens instantly. A nose may be enlarged, a smile sharpened, a posture bent into symbolism but the subject remains unmistakable. This balance between distortion and accuracy is the discipline’s defining challenge. Caricature does not abandon realism; it reorganizes it, prioritizing psychological and social truth over photographic precision.

Historically, caricature has thrived wherever societies permitted visual dissent. From Renaissance Italy’s playful studio sketches to the biting political prints of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe, caricature matured alongside public debate. As printing expanded, caricature moved from private amusement to public commentary, shaping how audiences understood leaders, celebrities, and social norms.

Today, caricature exists everywhere: in newspapers, museums, digital platforms, street markets, and social media feeds. New technologies have changed how caricatures are produced and shared, but not why they resonate. In an age saturated with images, caricature remains effective precisely because it simplifies without flattening. It reminds viewers that faces are never neutral and that exaggeration, when done well, can reveal what polite realism often hides.

Origins and Early Development

The origins of caricature stretch back further than the word itself. Long before formal terminology existed, artists were exaggerating human features to provoke laughter or reflection. Ancient Roman graffiti and marginal drawings already showed distorted faces used to mock authority and social types. Yet caricature as a deliberate artistic method emerged most clearly during the Italian Renaissance.

In late sixteenth-century Bologna, artists associated with the Carracci family began sketching exaggerated portraits for amusement and study. These drawings were not insults but exercises—ways to sharpen observation by isolating distinctive traits. The Italian verb caricare, meaning “to load” or “to exaggerate,” captured the method perfectly: the artist loaded the image with emphasis.

Seventeenth-century artists expanded the practice. Gian Lorenzo Bernini, best known for monumental sculpture, produced caricature drawings that distilled personality with astonishing economy. His sketches demonstrated that exaggeration could coexist with elegance and psychological insight.

By the eighteenth century, caricature escaped the studio. Advances in printmaking allowed images to circulate widely, transforming caricature into a public art form. England, with its relatively permissive press culture, became a center of satirical prints. Artists like William Hogarth and James Gillray used caricature to comment on politics, class, and morality, embedding exaggerated faces within complex narrative scenes.

This transition from private sketch to public statement changed caricature’s role permanently.

| Period | Development | Cultural Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Antiquity | Informal exaggeration | Social mockery |

| Renaissance | Artistic method | Observation and identity |

| 17th century | Elite practice | Psychological portraiture |

| 18th century | Print circulation | Political satire |

| 19th century onward | Mass media | Public opinion shaping |

The Language of Exaggeration

Caricature works because human perception is selective. When people recognize a face, they do not process every feature equally. Certain traits shape of the nose, spacing of the eyes, posture, habitual expressions carry more identity weight than others. Caricaturists exploit this cognitive shortcut by amplifying what the mind already notices.

The process is analytical rather than chaotic. Successful caricature begins with careful observation: how a person smiles, tilts their head, occupies space. The artist then exaggerates these elements in proportion to their psychological importance. A powerful figure may be drawn physically inflated; a nervous personality rendered with sharp angles and compressed posture.

This distinguishes caricature from general cartooning. Cartoons often focus on situations or fictional characters, using stylization broadly. Caricature, by contrast, is anchored to a specific individual. Recognition is essential. If the viewer cannot identify the subject, the caricature fails regardless of technical skill.

Art theorists often describe caricature as “selective realism.” It is not about distortion for its own sake, but about reorganizing reality to highlight meaning. In this sense, caricature functions as visual editing—cutting away the incidental to foreground the revealing.

Caricature as Social and Political Commentary

Caricature’s most influential role has been as a vehicle for social and political critique. In nineteenth-century France, caricature became a battleground between artists and authority. Satirical journals published exaggerated depictions of politicians, monarchs, and judges, turning facial distortion into political argument. These images communicated complex critiques instantly to a largely literate public.

Artists like Honoré Daumier demonstrated that caricature could be both humorous and morally serious. His works exposed hypocrisy, corruption, and class injustice, often at personal risk. Governments understood caricature’s power precisely because it was accessible. A single image could undermine authority more effectively than pages of text.

In Britain, caricature shaped public perception of international conflict and leadership. Exaggerated portrayals of Napoleon, for example, influenced how generations imagined him shorter, more aggressive, more theatrical than historical reality. These images became part of collective memory.

The same pattern persists today. Editorial caricature remains a cornerstone of newspapers worldwide. Even in digital form, exaggerated faces retain their potency because they condense opinion into visual shorthand.

| Medium | Primary Function | Audience Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Satirical prints | Political critique | Opinion formation |

| Newspapers | Editorial commentary | Public debate |

| Magazines | Cultural satire | Social reflection |

| Digital media | Rapid dissemination | Viral influence |

Caricature’s strength lies in its ability to bypass rational defenses and speak directly to intuition.

Caricature Beyond Politics

While politics brought caricature prominence, the form has always extended beyond governance. Social caricature flourished in the nineteenth century, depicting aristocrats, professionals, and urban life with affectionate irony or biting critique. These images documented manners, fashion, and class divisions more vividly than formal portraits ever could.

In entertainment contexts, caricature found new homes. Vaudeville posters, theater programs, and later magazine covers used exaggerated likenesses to market performers and personalities. The goal shifted from critique to recognition and appeal, but the underlying techniques remained the same.

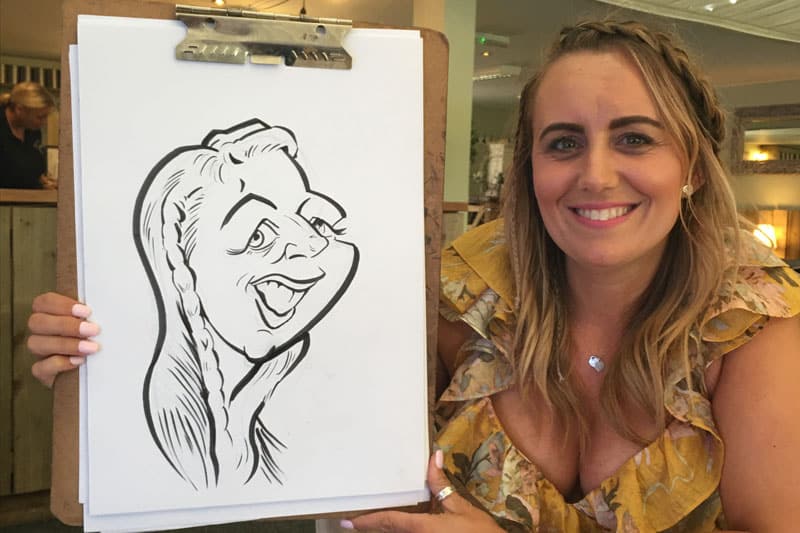

Caricature also became a popular form of live performance. Street and event artists produce rapid caricatures that blend technical skill with interpersonal engagement. In these settings, exaggeration becomes collaborative; subjects often enjoy seeing their defining traits amplified.

Cultural scholars note that this playful acceptance of distortion reflects a broader truth: caricature works best when audiences recognize exaggeration as interpretation rather than insult. It requires a shared understanding that likeness can be emotional, not literal.

Modern Caricature and Digital Transformation

The digital age has not replaced caricature; it has multiplied it. Software tools allow artists to exaggerate features with speed and precision, while social platforms distribute images instantly across borders. At the same time, artificial intelligence has introduced automated caricature filters that mimic exaggeration through algorithms.

Despite these innovations, traditional skills remain central. Digital caricature still depends on human judgment: which features matter, what exaggeration communicates character rather than mockery. Technology accelerates execution but does not replace perception.

Modern caricature also intersects with meme culture. Simplified, exaggerated faces circulate as symbols of attitudes and identities, often detached from specific individuals. This evolution expands caricature’s scope from portraiture to archetype.

Yet ethical questions persist. Exaggeration can reinforce stereotypes if handled carelessly. Contemporary caricaturists increasingly navigate boundaries around representation, power, and cultural sensitivity. The medium’s effectiveness depends on trust between artist and audience.

Visual communication experts emphasize that caricature survives because it adapts without losing its core logic: exaggeration as insight.

Caricature as Visual Psychology

Beyond art and media, caricature has attracted interest from psychologists studying perception and recognition. Research shows that people often recognize caricatured faces more easily than accurate photographs because exaggeration sharpens distinctive cues. This phenomenon helps explain why caricature feels intuitive rather than confusing.

By pushing features away from an average face, caricature increases contrast. The brain processes these deviations efficiently, reinforcing identity. In this sense, caricature aligns with how memory works favoring extremes over averages.

This psychological dimension explains caricature’s durability across cultures. While styles vary, the underlying mechanism remains universal. Humans recognize difference before detail, pattern before precision.

Experts in visual cognition often describe caricature as an artistic mirror of mental shortcuts. It externalizes how people already see, making implicit judgments explicit.

Takeaways

- Caricature is a disciplined art based on selective exaggeration, not random distortion.

- Its roots lie in Renaissance observation and expanded through print culture.

- Political caricature has shaped public opinion across centuries.

- Recognition depends on psychological perception as much as artistic skill.

- Digital tools expand reach but do not replace human judgment.

- Ethical use of exaggeration remains central to credibility.

Conclusion

Caricature endures because it understands something fundamental about human vision and judgment. We do not see the world neutrally; we notice patterns, fixate on differences, and assign meaning to faces. Caricature makes this process visible. By exaggerating what matters most, it reveals character, power, and contradiction with clarity that realism often cannot match.

Across centuries, caricature has adapted to new technologies, audiences, and cultural norms without losing its essence. It has mocked kings, elevated performers, challenged authority, and entertained strangers in public squares. In each context, it has served as both mirror and commentary.

In a visual culture overwhelmed by images, caricature’s discipline its insistence on observation, selection, and intention feels increasingly relevant. It reminds us that distortion, when guided by insight, can bring us closer to truth than faithful replication ever could.

FAQs

What defines a caricature?

A caricature exaggerates distinctive features of a real subject to reveal identity, character, or social meaning while remaining recognizable.

Is caricature meant to insult?

Not necessarily. While it can criticize, caricature often aims to interpret rather than demean, depending on context and intent.

How is caricature different from cartoons?

Caricature focuses on specific individuals, while cartoons often depict fictional characters or generalized situations.

Why are caricatures easy to recognize?

They amplify the features the human brain already uses to identify faces, enhancing perceptual contrast.

Does digital caricature change the art form?

It changes production methods, but the core principles of observation and exaggeration remain the same.

APA References

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2024). Caricature and cartoon. Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/art/caricature-and-cartoon

Gombrich, E. H. (1982). The image and the eye: Further studies in the psychology of pictorial representation. Phaidon Press. https://www.phaidon.com

McCloud, S. (1993). Understanding comics: The invisible art. HarperCollins. https://www.harpercollins.com

Library of Congress. (2023). Political cartoons and caricature in history. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov

Tate. (2024). Caricature: Art term. Tate Museums. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/c/caricature