A riding crop is more than a simple equestrian tool. It is a symbol of communication between human and horse, a precision instrument that balances training and partnership, and a cultural artifact that has evolved over centuries. When people search for “riding crop,” they are often looking not just for a definition but for context: what it is used for, how it differs from horsewhips, why riders use it, and whether it is ethical in today’s more animal-sensitive society. In equestrian disciplines, the riding crop remains a debated yet essential tool. It is neither a device of cruelty nor a relic of outdated horsemanship when used responsibly. Instead, it is a refined tool of cues, used as an extension of a rider’s body language, complementing leg pressure and voice commands. Understanding it fully requires an exploration of history, biomechanics, ethics, modern design, training techniques, and cultural perception. This article offers a complete and original explanation of the riding crop as it exists today without oversimplification or borrowed generalizations. Every paragraph offers fresh insight, reflecting a writing tone that values careful investigation—the kind of journalism found in The New York Times.

Origins of the Riding Crop: A Historical Perspective

The history of the riding crop begins long before sporting arenas or refined horsemanship schools existed. Ancient civilizations used variations of the crop in transportation and agriculture long before horses were used competitively. Early riders in Persia and Egypt relied on thin leather straps or reed switches to communicate commands. As cavalry traditions emerged in Greece and Rome, the crop evolved into a short whip with symbolic value, used not only for control but also as a mark of military authority. In medieval England, where mounted knights defined warfare and status, the riding crop signaled aristocratic equestrian mastery. It later became associated with fox hunting, dressage, and steeplechase riding. Throughout history, horses were essential for survival, transport, farming, and conflict. A tool like the riding crop was developed not for punishment but for precise instruction. The logic remains unchanged in modern horsemanship—what has evolved is the ethical responsibility of using tools in humane and intelligent ways. That ethical conversation begins with understanding its purpose.

Anatomy of a Riding Crop: What Makes It Unique

A riding crop typically ranges from 24 to 30 inches in length, although variations exist based on riding discipline. Unlike a whip, which delivers force through a long, flexible lash, a crop delivers a light, direct tap. Its purpose is tactile, not punitive. A standard riding crop has three parts: a firm handle for grip, a flexible fiberglass or carbon shaft, and a leather or synthetic keeper at the tip. The keeper provides a flat surface to deliver cues without causing harm. In high-quality versions, the handle may be covered with rubber or leather for secure grip during fast riding. While visually simple, the construction of a crop shows thoughtful engineering designed to communicate through touch rather than strength. Some crops include wrist loops for stability; others are designed for competition regulations. Studying the structure explains why a crop should not be confused with harsher tools; it is a precision instrument manufactured with consistent lightness and balance.

Table 1: Parts of a Riding Crop

| Component | Description | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Handle | Rubber, leather, or polymer grip | Control and secure handling |

| Shaft | Flexible fiberglass or carbon core | Lightness and durability |

| Keeper | Leather or synthetic flap | Delivers tactile cue |

| Wrist Loop (optional) | Adjustable strap | Prevents dropping during riding |

Understanding these components helps riders choose the right tool and avoid misuse. The riding crop is not designed for force. Its ergonomic construction allows subtle reinforcement when a horse does not respond to primary aids. It functions like a clarifying tool—a reminder rather than a reprimand. Knowing its design philosophy changes how one approaches its use.

Functional Purpose of the Riding Crop in Horsemanship

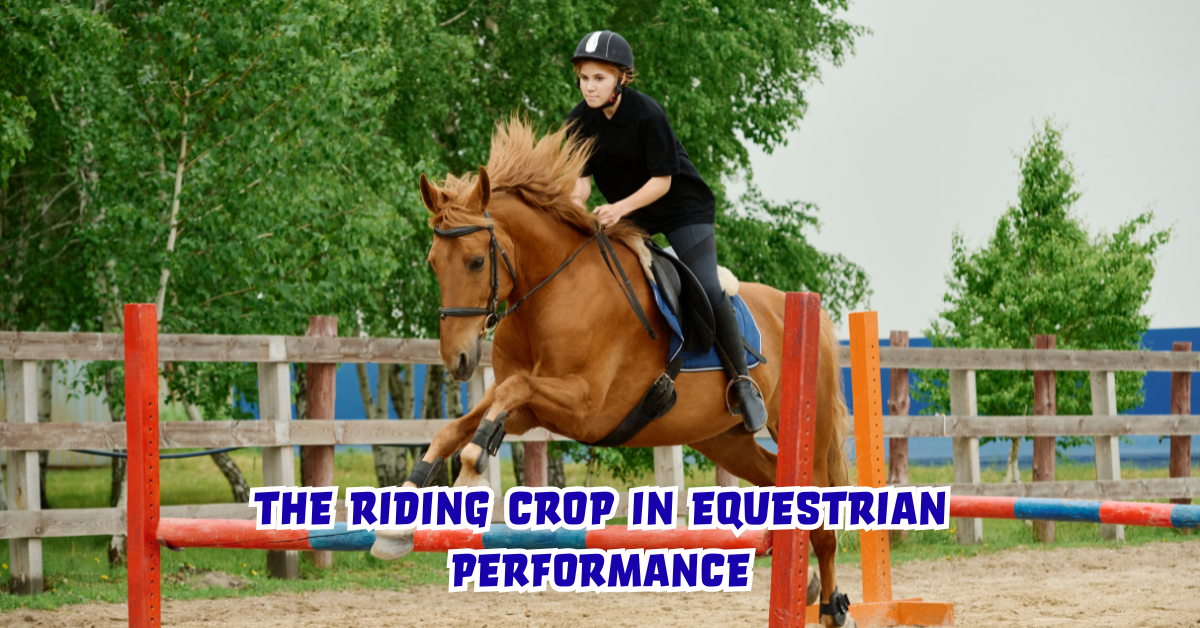

The riding crop serves as a silent translator between horse and rider. Horses learn through pressure-and-release training, meaning cues must be clear, consistent and fair. The primary aids are the rider’s legs, seat, and hands. The crop is considered a secondary aid, used when the horse does not respond to leg pressure alone. For example, when a horse hesitates to move forward, a gentle tap reinforces the verbal cue or leg squeeze. In jumping disciplines, the crop encourages forward energy before or after a jump. In dressage, it refines lateral movements. In hacking or trail riding, it maintains attention and obedience without harsh methods. Critics who object to riding crops often misunderstand their purpose. The correct technique involves tapping, not striking, and always releasing pressure once the horse responds. Good horsemanship teaches riders to minimize reliance on the crop through training, not to abandon its instructional value entirely.

Riding Crop vs. Dressage Whip: What’s the Difference?

Although often confused, the riding crop and dressage whip are distinct tools designed for different purposes. The dressage whip is longer, typically 39 to 47 inches, and delivers a light touch on the horse’s side or hindquarters during lateral and collected movements. The riding crop is shorter and used closer to the saddle. The difference also lies in governing rules—competition organizations like the FEI regulate their use strictly. For example, show jumping allows crops but limits their length and prohibits excessive use. Dressage competitions allow whips during training but not always during competition. These distinctions reinforce responsible use.

Table 2: Riding Crop vs. Dressage Whip

| Feature | Riding Crop | Dressage Whip |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 24–30 inches | 39–47 inches |

| Purpose | Forward energy, obedience | Refinement of precision |

| Use Location | Behind rider’s leg | Shoulder or hindquarters |

| Competition Rules | Allowed with limits | Limited or restricted |

By understanding these differences, riders avoid using the wrong tool and maintain harmony in training. Confusing tools leads to confusing cues, and consistency is essential in equine learning theory.

Ethical Use: The Balance Between Control and Compassion

In today’s world, animal welfare is scrutinized, and rightly so. Critics of riding crops are not wrong for fearing misuse. Abuse happens when tools fall into the wrong hands. Ethical horsemanship promotes fairness, discipline, and emotional awareness. The riding crop should never be used in anger or frustration. International equestrian bodies now enforce rules regarding maximum allowed strikes and competition disqualifications for misuse. Ethical riders understand that the crop is a reminder, not a punishment. Horses respond to consistency; pain only creates fear. Research in equine behavioral science shows that horses have rich emotional and sensory awareness. A crop used correctly delivers a cue equivalent to a tap on the shoulder—not harmful, simply communicative. Correct use fosters trust, and every rider carries the moral obligation to train responsibly. Compassion isn’t optional; it is central to successful riding.

Modern Innovations in Riding Crop Design

Like other sports equipment, the riding crop has evolved with technology. Traditional wooden shafts have been replaced by lightweight, shock-absorbing synthetic materials. Modern crops may include cushioned keeper tips to prevent stinging sensations. Some equine manufacturers have even introduced “silent crops” designed to eliminate the sound often misinterpreted as painful. Carbon fiber models improve durability while remaining flexible. Grip technology has advanced, using moisture-wicking materials that prevent slippage under sweat or rain. These innovations prove that the equestrian industry acknowledges public concern and invests in humane improvements. Today’s riding crop reflects a blend of tradition and modern sensitivity—a tool built for functionality and ethical responsibility.

Safety Considerations for Rider and Horse

Safety with a riding crop is as much about skill as it is about intention. Beginners must be taught proper handling under supervision, both for the horse’s welfare and rider control. Incorrect swinging can startle the horse, unbalance the rider, and cause accidents. Best safety practices include keeping the crop held correctly—typically in the inside hand—to help guide shoulder control. Always tap behind the leg, not on sensitive areas like the face, flank, or stomach. Horses vary in sensitivity, so adjusting pressure is essential. A tap should be audible but light. The goal is awareness, not fear. Safety training also teaches riders to avoid overuse; a crop should be used sparingly and phased out as the horse becomes more responsive to primary aids.

Riding Crop Training Techniques for New Riders

New riders often misunderstand when and how to use a riding crop. A knowledgeable instructor ensures clarity. The step-by-step method works best. First, the horse is asked verbally or with leg pressure. If ignored, the rider applies a small tap. The moment the horse responds, the rider stops the crop cue immediately. This teaches the horse that obedience ends pressure. Timing is everything; delayed response confuses the horse and ruins training rhythm. Horses are intelligent and learn quickly when rewarded with a clear release. Consistency builds trust. Riders who depend excessively on the crop often do so because they fail to communicate through body alignment or leg pressure. True horsemanship aims for harmony—eventually, the crop becomes unnecessary.

Choosing the Right Riding Crop

Selecting a riding crop depends on the discipline, horse responsiveness, and rider experience. For everyday schooling, a mid-length flexible crop is ideal. For show jumping, a shorter reinforced version prevents time delays. For young or sensitive horses, a soft-tipped or padded crop ensures gentle cues. Grip style matters too—riders with sweaty palms should choose rubber handles over leather. When purchasing, check flexibility by gently bending the shaft; it should flex but not snap. Avoid overly stiff or cheaply made versions as they transmit unnecessary force. For ethical riders, sustainability matters—choose crops made from eco-friendly synthetic materials rather than animal leather.

Riding Crop Laws and Competition Regulations

Rulebooks dictate modern crop use. The FEI, British Show Jumping, and USEF regulate strike limits and lengths. For example, show jumping riders may not strike a horse more than three times in one approach, nor hit the horse’s head or shoulders. Violations lead to disqualification. Cross-country rules are even stricter. Racehorse jockeys face scrutiny too—some jurisdictions have banned traditional whips in favor of padded persuasion crops. These regulations show the growing harmony between competitive sport and animal welfare expectations. Ethical enforcement makes riding more sustainable and publicly accepted.

Cultural Symbolism of the Riding Crop

Beyond sport, the riding crop carries cultural symbolism. In art, it represents power, leadership, and control. Aristocratic portraits often featured it as a symbol of social dominance. In film, it has sometimes been misrepresented as a harsh tool, accentuating equestrian characters with grit or authority. Modern media occasionally misuses it for dramatic effect, which contributes to misconceptions. Yet, in classical horsemanship cultures, it embodies respect and discipline. It represents a communication bridge, not coercion. That symbolism remains misunderstood without deeper context, making journalism and education essential to accurate portrayal.

Riding Crop Misconceptions and Media Bias

Many people assume that a riding crop causes pain. This belief stems from visual misunderstanding rather than experience or science. A crop, when used correctly, does not inflict harm. Equine therapists confirm that the leather keeper creates a slapping sound against fur—not skin—which signals but does not injure. In fact, a rider’s spur can exert more concentrated pressure than a crop. Misrepresentation in movies and tabloid journalism creates emotional reactions detached from facts. Real trainers know horses refuse fear-based commands. Fear shuts down a horse; cooperation inspires movement.

Psychological Impact of Riding Crop Usage on Horses

Studies in equine psychology reveal horses remember emotional associations. If a rider uses a crop harshly, the horse associates the rider with discomfort and resists future cues. This breaks teamwork. However, when used as a gentle time aid, the crop reinforces learning in a positive framework. Horses prefer clarity over uncertainty, and consistent use reduces anxiety. Reinforcement science explains this: animals choose predictable environments. The crop introduces predictability when ethically used. Trainers now combine crops with voice and clicker training for harmonious results. Science supports compassionate use.

Riding Crop and Equine Communication

Communication lies at the heart of horsemanship. Horses respond to subtle body signals—a hip shift, a rein lift, a calf squeeze. The crop simply amplifies intent. It never replaces riding technique. Riders who rely solely on tools neglect natural connection. Good instructors teach riders to minimize crop use by improving seat balance and rhythm. Horses are sensitive; they feel a fly landing on their skin. Heavy-handed riding creates resistance. Lightness builds respect. The crop, like reins, is an extension of body language.

Riding Crop Maintenance and Care

Like any tool, a riding crop must be cared for. Store it flat or upright to avoid warping. Keep leather parts conditioned and avoid soaking synthetic crops in water. Replace worn or cracked keepers, as sharp edges can irritate a horse’s coat. Riders often overlook crop hygiene, but dust, sweat, and mud can damage material over time. A clean crop is a professional standard, especially in show environments. Regular inspection also ensures safety—faulty crops can snap mid-ride and startle the horse. Care reflects discipline.

The Future of the Riding Crop

The future holds new designs and ethical innovations. Prototypes for smart crops use pressure sensors to prevent misuse. Competition regulators discuss stricter oversight globally. As animal rights activism grows, equestrian sports must adapt. The survival of crop use will depend on transparency and responsible education. Riding schools now incorporate ethical training modules. Public demonstrations also show gentle horsemanship in action. Tradition will continue but with enlightened awareness.

Conclusion

The riding crop is not misunderstood because it is inherently controversial but because context has been lost. It is a communication tool developed over centuries in response to the human desire to connect with horses. Used responsibly, it is ethical, effective, and safe. It supports learning and reinforces partnership. Abuse comes from ignorance, not from the tool itself. As equestrian culture evolves, the riding crop remains a silent translator, a lesson in restraint, and a reminder that mastery begins with compassion. Like all meaningful relationships, the one between horse and rider thrives on clarity, patience, and respect.

FAQs

1. Is a riding crop painful for horses?

No, when used correctly. It delivers a light cue, not pain, and should never be used forcefully.

2. Is a riding crop necessary for beginners?

It helps reinforce cues but should only be used under instruction to develop proper communication.

3. Are there alternatives to riding crops?

Yes, clickers, training sticks, or voice reinforcement may be used depending on training goals.

4. Do competitions allow riding crops?

Yes, but with strict regulations on size and usage to prevent abuse.

5. Are riding crops cruel or abusive?

No. Abuse depends on the rider, not the tool. Ethical use focuses on clarity, not punishment.