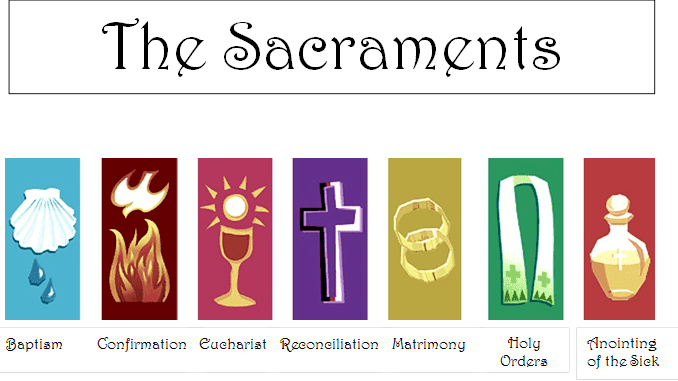

The seven sacraments occupy a central place in Roman Catholic life, functioning as both spiritual milestones and communal anchors. Baptism, Confirmation, the Eucharist, Reconciliation, Anointing of the Sick, Matrimony, and Holy Orders are understood not simply as ceremonies, but as effective encounters with divine grace. In Catholic teaching, they are outward signs that actually accomplish what they signify, making God’s presence tangible in water, oil, bread, wine, vows, and human touch.

Within the first hundred words, the core idea is this: the sacraments structure the entire Christian life. From initiation into the Church, through moments of failure, suffering, commitment, and service, they form a coherent spiritual framework. This sacramental system did not appear fully formed at Christianity’s beginning. Rather, it emerged gradually, shaped by scripture, early Christian practice, theological debate, and pastoral need. By the medieval period, the Church formally identified seven sacraments as normative, a structure later reaffirmed in response to the upheavals of the Reformation.

Beyond doctrine, sacraments shape daily and generational life. They accompany births and deaths, weddings and illnesses, personal crises and communal celebrations. For believers, they offer continuity in a changing world, connecting contemporary lives with centuries of ritual memory. This article explores how the seven sacraments developed, what each signifies, and why they continue to matter not only as theological concepts, but as lived practices embedded in culture, history, and human experience.

What a Sacrament Is in Catholic Theology

In Catholic theology, a sacrament is defined as an outward sign instituted by Christ to give grace. This definition emphasizes two inseparable dimensions. First, sacraments are visible and physical, involving material elements and human actions. Second, they are believed to communicate invisible spiritual realities divine life, forgiveness, healing, and mission.

This understanding rests on a deeply incarnational worldview. If God became flesh in Jesus Christ, then material reality itself becomes a vehicle of grace. Water cleanses, oil strengthens, bread nourishes, and spoken vows bind not merely symbolically, but sacramentally. The Church teaches that sacraments operate ex opere operato, meaning their effectiveness depends on God’s action through the rite, not on the personal holiness of the minister.

Over time, the Church grouped the sacraments into three categories: initiation, healing, and service. This structure reflects the arc of Christian life itself, from entry into faith, through renewal and restoration, toward responsibility for others. Together, the sacraments form what theologians call the “sacramental economy,” the ordinary means through which grace is encountered in the Church.

The Sacraments of Initiation

The sacraments of initiation Baptism, Confirmation, and the Eucharist establish the foundation of Christian life. They are traditionally received in sequence and mark progressive incorporation into the Church.

Baptism: Entry into New Life

Baptism is the gateway to all other sacraments. Through the pouring or immersion in water and the invocation of the Trinity, the baptized person is believed to be cleansed of sin and reborn into new life in Christ. The rite symbolizes both death and resurrection: dying to an old way of life and rising into communion with God and the Church.

Historically, baptism was often administered to adults after a lengthy period of preparation. Over time, infant baptism became the norm in much of the Catholic world, reflecting the belief that grace precedes conscious choice. Regardless of age, baptism establishes a permanent spiritual bond and is received only once.

Confirmation: Strengthening the Baptismal Gift

Confirmation builds upon baptism by sealing the believer with the gifts of the Holy Spirit. Through the laying on of hands and anointing with sacred oil, the Church prays for spiritual strength, maturity, and courage. Confirmation emphasizes personal responsibility within the faith community, often coinciding with adolescence or early adulthood.

While baptism incorporates a person into the Church, confirmation deepens that belonging, equipping believers to witness publicly to their faith. In this sense, it bridges personal belief and communal mission.

Eucharist: The Center of Catholic Life

The Eucharist, or Holy Communion, holds a unique place among the sacraments. Catholics believe that bread and wine, consecrated during the Mass, become the real presence of Christ. Participation in the Eucharist is seen as spiritual nourishment, sustaining believers in daily life.

Often described as the “source and summit” of Christian life, the Eucharist unites individuals with Christ and with one another. It is not only a personal devotion but a communal act that expresses and creates unity within the Church.

The Sacraments of Healing

Human life is marked not only by beginnings but by failure, suffering, and vulnerability. The sacraments of healing Reconciliation and Anointing of the Sick address these realities directly.

Reconciliation: Restoration of Communion

Reconciliation, also called Confession or Penance, responds to the reality of sin and broken relationships. In this sacrament, individuals confess their sins to a priest, express repentance, and receive absolution. The rite emphasizes God’s mercy and the possibility of renewal.

Historically, practices of penance varied widely, from public acts of reconciliation in the early Church to the private confessional familiar today. Despite these changes, the core meaning remains constant: reconciliation restores communion with God and the Church, reaffirming that failure is not the final word.

Anointing of the Sick: Grace in Suffering

Anointing of the Sick offers spiritual strength to those facing serious illness, surgery, or the frailty of old age. Through prayer and anointing with oil, the Church asks for healing, comfort, and peace. While physical healing may occur, the sacrament primarily addresses spiritual endurance and trust.

Formerly associated almost exclusively with imminent death, the sacrament has been reemphasized as a source of grace at many points of serious illness. It reflects a theology that does not deny suffering, but seeks meaning and presence within it.

The Sacraments of Service and Commitment

The final two sacraments Matrimony and Holy Orders orient believers toward service of others. Rather than focusing primarily on individual sanctification, they structure communal life.

Matrimony: Covenant and Faithful Love

Matrimony sanctifies the lifelong union of a baptized man and woman. In Catholic teaching, marriage reflects Christ’s faithful love for the Church and is ordered toward mutual support and the raising of children. The spouses themselves administer the sacrament through their exchange of vows.

Marriage is understood not merely as a private contract, but as a public covenant with spiritual and social dimensions. Its sacramental character affirms the dignity of family life and the sacredness of ordinary love.

Holy Orders: Service and Leadership

Holy Orders consecrates men as deacons, priests, or bishops, entrusting them with preaching, sacramental ministry, and pastoral leadership. Through the laying on of hands, the Church recognizes a vocation to serve the community in a distinctive way.

The sacrament emphasizes continuity with the apostolic tradition, linking contemporary ministry to the earliest Christian communities. In this sense, Holy Orders functions as a sacrament of memory, preserving the Church’s teaching and sacramental life across generations.

Historical Development of the Seven Sacraments

The number and understanding of sacraments evolved gradually. Early Christians recognized many sacred actions but did not immediately settle on a fixed list. Over time, theological reflection and pastoral practice converged.

By the early thirteenth century, Church authorities formally identified seven sacraments as normative. This structure was later reaffirmed during major councils in response to theological disputes of the Reformation era. The number seven itself carried symbolic weight, associated with completeness in biblical tradition.

This historical development illustrates that sacramental theology is not static. It emerged through dialogue between scripture, tradition, and lived experience, adapting to new contexts while maintaining continuity with the past.

Comparative Overview of the Seven Sacraments

| Category | Sacrament | Core Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Initiation | Baptism | New life and entry into the Church |

| Initiation | Confirmation | Strengthening by the Holy Spirit |

| Initiation | Eucharist | Spiritual nourishment and communion |

| Healing | Reconciliation | Forgiveness and restoration |

| Healing | Anointing of the Sick | Comfort and grace in suffering |

| Service | Matrimony | Covenant love and family life |

| Service | Holy Orders | Leadership and sacramental ministry |

Sacraments Across the Life Cycle

| Life Stage | Sacramental Presence |

|---|---|

| Birth and childhood | Baptism, early Eucharist |

| Adolescence | Confirmation |

| Adult life | Eucharist, Reconciliation |

| Commitment | Matrimony or Holy Orders |

| Illness and aging | Anointing of the Sick |

| Death and remembrance | Eucharist and funeral rites |

Expert Reflections on Sacramental Life

“Sacraments create a rhythm of grace that accompanies believers through every stage of life, integrating theology with lived experience.” — Scholar of sacramental theology

“The power of the sacraments lies in their ability to hold together memory, community, and hope across centuries.” Historian of Christianity

“Catholic sacramental practice insists that grace is not abstract but encountered through ordinary human realities.” Liturgical theologian

Takeaways

- The seven sacraments structure Catholic spiritual life from beginning to end.

- They are grouped into initiation, healing, and service, reflecting stages of faith.

- Sacraments combine material signs with spiritual meaning.

- Their current form developed gradually through history and councils.

- Healing sacraments address sin and suffering directly.

- Service sacraments orient believers toward others and community.

- Together, they express a deeply incarnational theology.

Conclusion

The seven sacraments represent more than a theological system; they are a lived map of Catholic existence. Through water and oil, bread and vows, confession and blessing, they weave grace into the ordinary contours of life. Their endurance lies not only in doctrine, but in their capacity to accompany human experience joy and failure, love and loss, birth and death.

Across centuries of change, the sacraments have remained recognizable yet adaptable, grounded in tradition while responding to new pastoral realities. For believers, they offer continuity in a fragmented world and a language for encountering the sacred within the everyday. Whether approached with deep faith or cultural familiarity, the seven sacraments continue to shape identity, memory, and community in ways few religious practices have matched.

FAQs

What are the seven sacraments in Catholicism?

They are Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, Reconciliation, Anointing of the Sick, Matrimony, and Holy Orders.

Why are sacraments important to Catholics?

They are believed to confer grace and structure spiritual life from birth to death.

Can all sacraments be repeated?

Some can, such as Reconciliation and Eucharist; others, like Baptism, are received only once.

Do other Christians recognize seven sacraments?

Some traditions recognize fewer sacraments or understand them differently.

Are sacraments only symbolic?

In Catholic theology, sacraments are effective signs that truly communicate grace.

APA References

Britannica Editors. (n.d.). The seven sacraments of the Roman Catholic Church. Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Wikipedia Contributors. (2025). Sacraments of the Catholic Church.

U.S. Catholic. (2023). Why are there seven sacraments?

The Cathedral of Saint Patrick. (n.d.). The Seven Sacraments.

St. James Catholic Church. (n.d.). The Seven Sacraments.